What's the evidence for this claim? Let's start by briefly explaining what the H-index is. It's computed by rank ordering a set of publications in terms of their citation count, and identifying the point where the rank order exceeds the number of citations. So if a person has an H-index of 20 this means that they've published 20 papers with at least 20 citations – but their 21st paper (if there is one) had fewer than 21 citations.

The reason this is reckoned to be relatively impervious to gaming is that authors don't, in general, have much too much control over whether their papers get published in the first place, and how many citations their published papers get: that's down to other people. You can, of course, cite yourself, but most reviewers and editors would spot if an author was citing themselves inappropriately, and would tell them to remove otiose references. Nevertheless, self-citation is an issue. Another issue is superfluous authorship: if I were to have an agreement with another author that we'd always put each other down as authors on our papers, then both our H-indices would benefit from any citations that our papers attracted. In principle, both these tricks could be dealt with: e.g, by omitting self-citations from the H-index computation, and by dividing the number of citations by the number of authors before computing the H-index. In practice, though, this is not usually done, and the H-index is widely used when making hiring and promotion decisions.

In my previous blogpost, I described unusual editorial practices at two journals – Research in Developmental Disabilities and Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders – that had led to the editor, Johnny Matson achieving an H-index on Web of Science of 59. (Since I wrote that blogpost it's risen to 60). That impressive H-index was based in part, however, on Matson publishing numerous papers in his own journals, and engaging in self-citation at a rate that was at least five times higher than typical for productive researchers in his field.

It seems, though, that this is just the tip of a large and ugly iceberg. When looking at Matson's publications, I found two other journals where he published an unusual number of papers: Developmental Neurorehabilitation (DN) and Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities (JDPD). JDPD does not publish dates of submission and acceptance for its papers, but DN does, and I found that for 32 papers co-authored by Matson in this journal between 2010 and 2014 for which the information was available, the median lag from a paper being received and it being accepted was one day. So it seemed a good idea to look at the editors of DN and JDPD. What I found was a very cosy relationship between editors of all four journals.

Figure 1 shows associate editors and editorial board members who have published a lot in some or all of the four journals. It is clear that, just as Matson published frequently in DN and JDPD, so too did the editors of DN and JDPD publish frequently in RASD and RIDD. Looking at some of the publications, it was also evident that these other editors also frequently co-authored papers. For instance, over a four-year period (2010-2014) there were 140 papers co-authored by Mark O'Reilly, Jeff Sigafoos, and Guiliano Lancioni. Interestingly, Matson did not co-author with this group, but he frequently accepted their papers in his journals.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of publication lags for the 140 papers in RASD and RISS where authors included the O'Reilly, Sigafoos and Lancioni trio. This shows the number of days between the paper being received by the journal and its acceptance. For anything less than a fortnight it is implausible that there could have been peer review.

|

| Figure 2 Lag from paper received to acceptance (days) for 73 papers co-authored by Sigafoos, Lancioni and O'Reilly, 2010-2014 |

Papers by this trio of authors were not only accepted with breathtaking speed: they were also often on topics that seem rather remote from 'developmental disabilities', such as post-coma behaviour, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Alzheimer's disease. Many were review papers and others were in effect case reports based on two or three patients. The content was so slender that it was often hard to see why the input of three experts from different continents was required. Although none of these three authors achieved Matson's astounding rate of 54% self-citations, they all self-cited at well above normal rates: Lancioni at 32%, O'Reilly at 31% and Sigafoos at 26%. It's hard to see what explanation there could be for this pattern of behaviour other than a deliberate attempt to boost the H-index. All three authors have a lifetime H-index of 24 or over.

One has to ask whether the publishers of these journals were asleep on the job, not to notice the remarkable turnaround of papers from the same small group of people. In the Comments on my previous post, Michael Osuch, a representative of Elsevier, reassured me that "Under Dr Matson’s editorship of both RIDD and RASD all accepted papers were reviewed, and papers on which Dr Matson was an author were handled by one of the former Associate Editors." I queried this because I was aware of cases of papers being accepted without peer review and asked if the publisher had checked the files: something that should be easy in these days of electronic journal management. I was told "Yes, we have looked at the files. In a minority of cases, Dr Matson acted as sole referee." My only response to this is, see Figure 2.

Reference

Hirsch, J. (2005). An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102 (46), 16569-16572 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102

P. S. I have now posted the raw data on which these analyses are based here.

P.P.S. 1st March 2015

Some of those commenting on this blogpost have argued

that I am behaving unfairly in singling out specific authors for criticism.

Their argument is that many people were getting papers published in RASD

and RIDD with very short time lags, so why should I pick on Sigafoos, O'Reilly,

and Lancioni?

I should note first of all that the argument 'everyone's

doing it' is not a very good one. It would seem that this field has some pretty

weird standards if it is regarded as normal to have papers published without

peer review in journals that are thought to be peer-reviewed.

Be this as it may, since some people don't seem to have understood the blogpost, let me state more explicitly the reasons why I have singled out these

three individuals. Their situation is different from others who have achieved

easy reviewer-free publication in that:

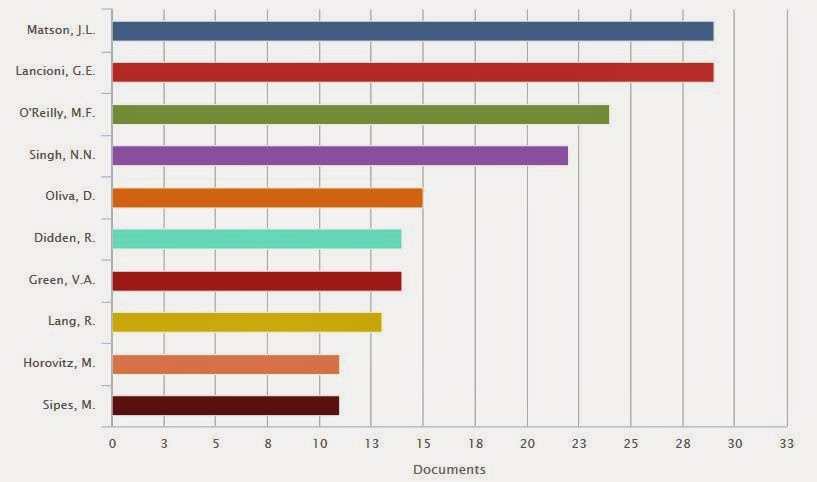

1. Their publications don't only seem to get into RIDD and

RASD very quickly; they also are of a quite staggering quantity – they eclipse

all other authors other than Matson. It's easy to get the stats from Scopus, so

I am showing the relevant graphs here, for RIDD/RASD together and also for the

other two journals I focused on, Developmental Neurorehabilitation and JDPD.

| ||

| Top 10 authors RASD/RIDD 2010-2014: from Scopus |

| |

| Top 10 authors 2010-2014: Developmental Neurorehabilitation (from Scopus) |

|

| Top 10 authors 2010-2014: JDPD (from Scopus) |

2. All three have played editorial roles for some of these four

journals. Sigafoos was previously editor at Developmental Neurorehabilitation,

and until recently was listed as associate editor at RASD and JDPD. O'Reilly is editor of JDPD, is on the

editorial board of Developmental Neurorehabilitation and was until 2015 on the

editorial board of RIDD. Lancioni was

until 2015 an associate editor of RIDD.

Now if it is the case that Matson was accepting papers for

RASD/RIDD without peer review (and even my critics seem to accept that was

happening), as well as publishing a high volume of his own papers in those

journals, then that is something that is certainly not normally accepted

behaviour by an editor. The reasons why journals have editorial boards is

precisely to ensure that the journal is run properly. If these editors were

aware that you could get loads of papers into RASD/RIDD without peer review,

then their reaction should have been to query the practice, not to take

advantage of it. Allowing it to continue has put the reputation of these journals at risk. You might say why didn't I include other associate editors or

board members? Well, for a start none of them was quite so prolific in using

RASD/RIDD as a publication outlet, and, if my own experience is anything to go

by, it seems possible that some of them were unaware that they were even listed

as playing an editorial role.

Far from raising questions with Matson about the lack of

peer review in his journals, O'Reilly and Sigafoos appear to have encouraged

him to publish in the journals they edited. Information about publication lag

is not available for JDPD; in Developmental

Neurorehabilitation, Matson's papers were being accepted with such lightning speed

as to preclude peer review.

Being an editor is a high status role that provides many

opportunities but also carries responsibilities. My case is that these were not

taken seriously and this has caused this whole field of study to suffer a major

loss of credibility.

I note that there are plans to take complaints about my

behaviour to the Vice Chancellor at the University of Oxford. I'm sure he'll be

very interested to hear from complainants and astonished to learn about what

passes for acceptable publication practices in this field.

P.P.P.S 7th March 2015

I note from the comments that there are those who think that I should not criticise the trio of Sigafoos, O'Reilly and Lancioni for having numerous papers published in RASD and RIDD with remarkably short acceptance times, because others had papers accepted in these journals with equally short lags between submission and acceptance. I've been accused of cherry-picking data to try and make a case that these three were gaming the system.

As noted above, I think that to repeatedly submit work to a journal knowing that it will be published without peer review, while giving the impression that it is peer-reviewed (and hence eligible for inclusion in metrics such as H-index) is unacceptable in absolute terms, regardless of who else is doing it. It is particularly problematic in someone who has been given editorial responsibility. However, it is undoubtedly true that rapid acceptance of papers was not uncommon under Matson's editorship. I know this both from people who've emailed me personally about it, and there are also brave people who mention this in the Comments. However, most of these people were not gaming the system: they were surprised to find such easy acceptance, but didn't go on to submit numerous papers to RASD and RIDD once they became aware of it.

So should I do an analysis to show that, even by the lax editorial standards of RASD/RIDD, Sigafoos/O'Reilly/Lancioni (SOL) papers had preferential treatment? Personally I don't think it is necessary, but to satisfy complainants, I have done such an analysis. Here's the logic. If SOL are given preferential treatment, then we should find that the acceptance lag for their papers is less than for papers by other authors published around the same time. Accordingly, I searched on Web of Science for papers published in RASD during the period 2010-2014. For each paper authored by Sigafoos, I took as a 'control' paper the next paper in the Web of Science list that was not authored by any of the six individuals listed in Table 1 above, and checked its acceptance lag. There were 20 papers by Sigafoos: 18 of these were also co-authored by O'Reilly and Lancioni, and so I had already got their acceptance lag data. I added the data for the two additional Sigafoos papers. For one paper, data on acceptance lag was not provided, so this left 19 matched pairs of papers. For those authored by Sigafoos and colleagues, the median lag was 4 days. For papers with other authors, the median lag was 65 days. The difference is highly significant on matched pairs t-test; t = 3.19, p = .005. The data on which this analysis was based can be found here.

I dare say someone will now say I have cherrypicked data because I only analysed RASD and not RIDD papers. To that I would reply, the evidence for preferential treatment is so strong that if you want to argue it did not occur, it is up to you to do the analysis. Be warned, checking acceptance lags is very tedious work.